Inside the campaign to kill a London super venue

Locals have seen off a £800m glowing Goliath — here's how they did it

Morning — today’s story is an uncomfortable tale for any Londoner quick to hate on NIMBYism in their city. For five long years, Stratford residents have waged a war to stop their nightmare: a huge, glowing concert venue being built on their doorsteps. They were dealt a bad hand — an immensely rich opponent, unelected planners — and yet, last week, their opponent finally folded. For your big read this morning, we’ve gone inside the campaign to kill off the MSG Sphere — the highs, lows and downright bizarre.

Four quick things before that:

The iconic G-A-Y Late in Soho has announced its closing down next month. Owner Jeremy Joseph has blamed a lack of police presence in the area, making it too hard to keep customers and staff safe. Its sister venues, G-A-Y Bar and Heaven, are staying open.

Sadiq Khan gave evidence to the Covid Inquiry on Monday. The mayor’s big claim was that London representatives were excluded from early emergency meetings with central government, which in turn cost lives in the capital.

One of the last residents of the Aylesbury Estate, Southwark was in the High Court on Tuesday fighting her recent eviction. The council is bulldozing Aysen Dennis’s home of 30 years to make way for a new development.

More ultra-rapid chargers for electric vehicles are being rolled out in London. TfL is building new charger hubs in Hanger Lane, Canning Town, Hillingdon Circus, Hatton Cross and Tottenham Hale.

One more thing: Londoners don’t have a quality magazine for news about their city. We want to change that. By email to start, with digestible round-ups, detailed features and hard-hitting investigations. You can help us make it by pledging a subscription to the Spy. You won’t pay anything yet, but you’ll automatically become a paid member when we launch. Like a crowdfunding campaign, in slow-motion. All for less than a pint each month.

‘This isn’t NIMBYism. Nobody moves here and expects nothing to change.’

It was while looking at a tiny model of the Sphere at an information event in Westfield shopping centre, just hours after getting the keys to her new home in late 2018, when it all dawned on Ceren Sonmez. She recalls pointing out her flat in the miniature version of Stratford put on display. “That’s our new home!” Ceren said, before looking back at the model Sphere. “How does that fit in? How is that appropriate for a place like this?” A Sphere rep allegedly replied: "If you didn't want to live somewhere noisy, you shouldn't have chosen to live in Stratford.”

Not long afterwards, Ceren helped found Stop the MSG Sphere, a campaign group that declared victory last week when mayor Sadiq Khan blocked the proposed £800m super venue in east London. Over the past five years, the group has rallied locals, councillors and MPs against the 21,500-capacity venue, and ultimately forced a U-turn from Khan, who’d backed the Sphere when plans were first unveiled. “It’s great to welcome another world-class venue to the capital, to confirm London’s position as a music powerhouse,” Khan had originally said in a statement announcing the Sphere put out by the owners, the Madison Square Garden Company (MSG).

Many of the facts were already on Khan’s desk when he made that endorsement. A venue as wide as the London Eye and nearly as high as Big Ben, wrapped completely in LED screens that would beam concerts and adverts across east London, plonked in a dense residential area already burnt by the legacy of the 2012 Olympics. It’s a carbon copy of a Sphere that opened in Las Vegas this September with an inaugural concert from U2, featuring dazzling panoramic visuals.

Unrelenting efforts from locals have undoubtedly helped kill off London’s version. By the time of Khan’s decision last Monday, practically all of the area’s local politicians were voicing opposition to the Sphere. To get there, the campaign has battled a global entertainment giant, a board of unelected planners and, at times, a faceless third party deploying underhand tactics. It’s a story that exposes the uglier side of building London’s mega projects — and perhaps reveals the limits of YIMBYism in the capital too. But it also shows the city’s grassroots campaigns still pack a punch, even when against those with deep pockets.

Back in October 2018 though, Ceren had no idea of what lay ahead when she arrived in Stratford with her new house keys. She and her husband had bought a flat in Legacy Tower, one of the buildings they’d only later realise would be closest to the Sphere. “We were super duper excited,” she says, in conversation with the Spy. “It’d been a long process, using a first-time homebuyer scheme, and we never thought we'd own a flat. But here we were, amazing, got our key, after all the struggles.”

As she walked into the lobby area of her building that first day, she spotted a stack of fliers. They were from MSG, leaflets about the Sphere and advertising the consultation. It was the first time Ceren had seen the plans. Worry kicked in. “We were like, ‘What is that? And where is it going to be built? That's very strange.’”

After attending the MSG consultation in Westfield, Ceren was left deeply disappointed — and determined. She soon found out she wasn’t alone, coming across others on local Facebook groups also expressing concern about the Sphere. “I discovered a couple more people who had already joined forces and were getting things up and running in terms of like, residents against the Sphere. And so I joined right at its inception.”

The campaign’s first meeting was held at someone’s flat in Stratford later in 2018, still before MSG’s plans had been officially submitted. Ceren says the group of rebels was made up of “locals of varying distance” from the Sphere, with their top priority for the campaign depending on how far away they lived. Those closest to the planned location — a site that had been used as a coach park during the Olympics, near Westfield — feared the noise and light pollution most. Not only from concerts, but from the adverts that MSG planned to display on the Sphere’s outer shell during the day. A glorified billboard on their doorstep, they feared. Residents slightly further away were more focused on the implications of another 20,000-capacity venue on the Jubilee Line. Their doomsday scenario was simultaneous concerts at the Sphere and the nearby O2 Arena paralysing local trains and buses. Others prioritised the environmental impact — Hackney Marshes aren’t far, and they questioned what all that light would do to wildlife. All agreed, though, that the Sphere had to be stopped.

Except they had a curveball to contend with, one unique to the Stratford area. They’d have to convince the London Legacy Development Corporation (LLDC) to block it.

The legacy

The campaigners the Spy has spoken to agree that Sphere would have been doomed from the start if it’d been proposed anywhere else in London. That’s because permission to build projects in the Stratford Olympic Park is overseen by a unique body — the LLDC — that operates at arm's length from locals.

The LLDC was set up after the 2012 Olympics, replacing the old organisation that had taken over swathes of east London to build infrastructure for the Games — stadiums, hotels and the like. To this day the legacy of hosting the Olympics in London is still hotly debated — whether the “orgy of development” that ensued has really benefitted locals. Olympic organisers were conscious that, a the turn of the millennium, Stratford and east London were very different to now — more rundown, and one of the most deprived parts of the UK. They hoped the Games would mean regeneration — and that bodies like LLDC would cement this legacy in the years following 2012.

But unlike the rest of the capital, where borough planning committees are made up entirely of elected councillors, seats on the LLDC’s planning committee aren’t directly voted in. There’s still some democratic oversight — just under half of the 12 seats are made up of councillors from the surrounding boroughs who’d given up some of their land for the Olympics. That included Newham — Stratford’s borough — but also Greenwich, Hackney, Tower Hamlets and Waltham Forest. But most LLDC planners are drawn from the world of business, not politics, and are appointed by the London mayor, not elected by voters. These appointees had enough seats to green-light the Sphere, even if all of the councillors on the board objected.

The challenge this posed for anti-Sphere campaigners was immense. This wouldn’t be a standard planning battle, where the threat of punishment at the ballot box could be dangled over local councillors’ heads. And campaigners say this was something MSG had banked on.

Among the politicians who came to back their campaign, Stop the MSG Sphere consistently point to Nate Higgins, a Green councillor for Newham, as their main champion. Since 2022 he’s represented Stratford Olympic Park, the ward where the Sphere was going to be built, and he’s quick to praise campaigners like Ceren when speaking to the Spy. He’s clear in his view that, if a normal borough had the final say, MSG wouldn’t have bothered, “because it’s so obviously not in residents’ interests”.

He continues: “I think MSG saw their chance — their chance to try and get something through, where the views of residents are shut out of the process — and they went for it.”

Campaigners were nervous for the looming LLDC decision, but undeterred. Their immediate priority was to “drum up attention”, according to Ceren. She explains: “These were pre-Covid days when we would go door knocking and talk to residents and all our neighbours. It was how I got to meet everybody in my building. They all received a leaflet that I'd made and printed, and I was like, ‘Did you know this thing is being proposed to be built here?’”

Both Stratford’s post-Olympic new builds and the pre-Olympic estates and high rises were targeted by Ceren and her squad of canvassers. The biggest surprise on the ground was the lack of awareness that the Sphere was even in the pipeline. “We were finding that hundreds of people had no idea — the people who would be most affected by this had absolutely no idea that this thing was proposed to be built on our doorstep.”

By March 2019, MSG had officially submitted plans for the Sphere. But relations between the company and the campaigners had frozen up, after a few brief interactions at the start. Ceren says she’d initially been messaged by someone from MSG on Facebook, but: “I don't think I responded, because I'd had such a negative experience with them at the other consultation. I was just like, they're a gigantic company, I don't really want to meet with them as an individual, I'm not interested in having this discussion at this point. I don't know enough, I'm intimidated by by the thought of meeting up with them again, and them shutting me down again.” From then on the campaign had little contact — let alone sit-downs — with the Sphere’s owners, aside from crossing paths with reps at council meetings. At times it felt like, to campaigners, MSG was denying their campaign even existed.

That question of existence would soon be drawn into sharp focus. Stop the MSG Sphere seemingly had competition — they weren’t the only ones claiming to represent local residents.

Astroturfed

The most bizarre chapter of the story involves another player with a clear interest in the fate of the Sphere — the owners of the O2 Arena in Greenwich, AEG Europe. In 2019 the company was accused of paying for an astroturfing campaign that used a “fake” grassroots community organisation to try to whip up local opposition to the Sphere.

The O2 Arena is just across the river from the Sphere’s proposed spot, inside the Millennium Dome, and is right now the largest dedicated concert venue in London, with a 20,000 capacity. The Sphere would have topped that, with a 21,500 capacity when using a mix of seated and standing arrangements, while also offering concert-goers cutting-edge tech, designed by architects Populus. Aside from the huge screens, which wrap around the entirety of the dome and display tailored visuals for concerts, the Sphere is equipped to give a ‘4D’ experience, featuring seats with haptic feedback and even a system that can waft scents and wind through the arena. Reviews of the first Sphere shows in Las Vegas have been gushing — “mind-expanding”, “utterly astonishing”, “reinventing the 21st-century live experience”.

AEG Europe were clearly spooked. According to a report in the Times published in June 2019, the company decided to hire a PR firm, Sans Frontières Associates (SFA), to wage a “secretive campaign” to stop London’s Sphere. SFA bought out billboard space around Stratford — one read “Say no: Stratford MSG Sphere” — and claimed the venue would cause more traffic and pollution. It also set up a social media presence. But SFA weren’t particularly upfront — they did so all under the mysterious name of Newham Action Group. The group’s description on social media stated it was a “page for residents by residents”.

Ceren initially reacted with delight — it seemed more residents were apparently campaigning against the Sphere. She even attempted to contact Newham Action Group, asking to join forces. But she says she never actually heard back with a proper message. “It was just a very, very strange time in the campaign,” she says.

And then, out of nowhere, the Newham Action Group disappeared online — just before the publication of the piece in the Times. Though grateful to finally understand what had gone on, the real campaign was caught in the blowback: they now faced doubts they were even real too. Ceren took to carrying her passport in her bag when she went door-knocking just to prove she was who she said she was.

“For a moment, it was really frustrating,” she says, “because people were also pointing the finger at us, that we were a faceless entity as well, and how convenient it is that we’re doing this and doing that. So there was definitely a phase of the campaign where there was some scepticism towards us as a group. And I just remember going out into the world so many times, and I was just like, ‘Look the difference is, I come to your doors, I knock on your doors, I talk to you, I show you things.’”

For cllr Higgins, AEG Europe was an unexpected — but not unhelpful — ally. “The O2 had a really clear commercial incentive to oppose it. I don't think anyone is naive to that fact,” he explains. “But also, I've actually met them, while I've never had any contact from MSG. And so you can't really blame them for engaging with communities to make the case for why this is a bad idea. They provided a genuinely useful perspective — that there'll be severe risks to the capacity of the Jubilee Line if this was to go ahead. That doesn't mean that we were naive to their incentives.”

Frustrating the campaign even further was MSG’s own attempts to represent residents — through a September 2019 poll that, the company claimed, had shown nearly unanimous backing for the Sphere: 85% in favour. The retort from campaigners was that the poll was of mostly outside visitors who didn’t live in Stratford. They pointed to the fact only 11% had even heard of the Sphere beforehand.

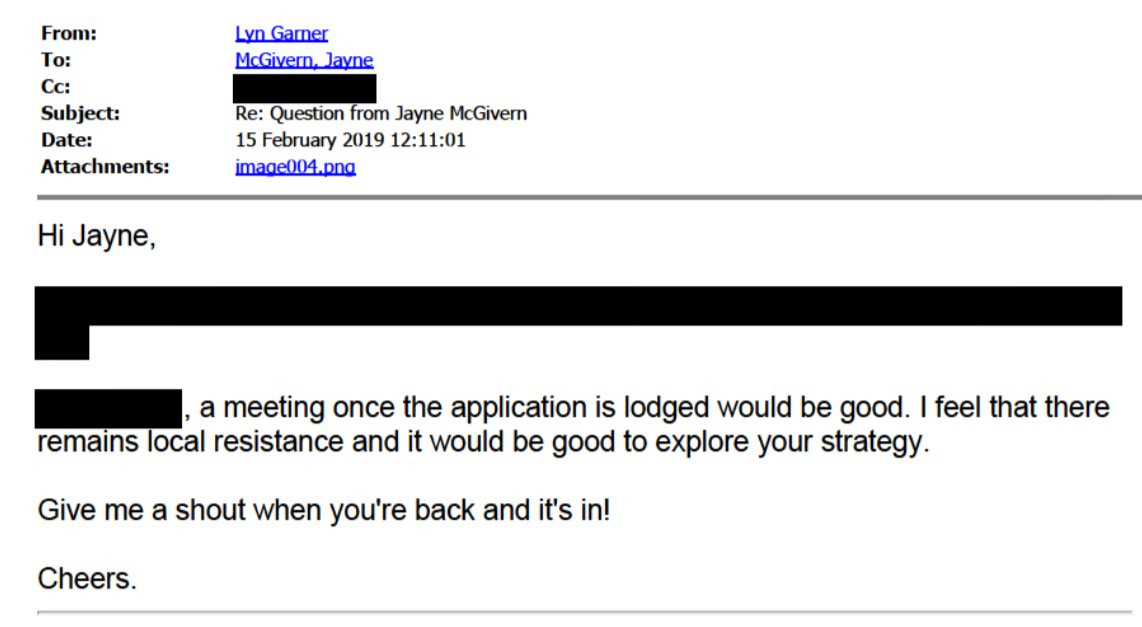

Stop the MSG Sphere had some tricks of their own to fight back with. Later in 2019, the group published internal emails it’d obtained via Freedom of Information showing conversations between MSG execs and members of the LLDC. One in particular raised backs — sent in February 2019 by Lyn Garner, the CEO of the LLDC, to Jayne McGiven, MSG’s president of development and construction. After asking for a meeting with MSG once it had lodged its planning application, Garner wrote: “I feel that there remains local resistance and it would be good to explore your strategy”. Campaigners saw the email as the smoking gun that the relationship between planners and MSG had become too cosy, and that the process was stacked against them.

It was obvious to the LLDC board that passions were high. The can kept being kicked down the road, with extra public consultations ordered and the decision delayed. But eventually, a date was agreed to decide on the Sphere — a make-or-break meeting on March 22, 2022.

The setback

On the eve of LLDC’s decision meeting, Stop the MSG Sphere had, on paper, done everything right. Their message was being amplified by pretty much every local politician in the area. Newham council were officially against the plans, having lodged several planning objections, and lamented it was only represented by two councillors on the LLDC’s planning committee of 12. The MP for West Ham, Lyn Brown, was writing in national newspapers to call the Sphere a “monstrous glowing orb”, and she had a statement read out at the planning meeting supporting campaigners. Opposition cut across party lines — both Labour and Greens, the two main political forces in the Newham area.

And it wasn’t just the campaign that was objecting to the Sphere. MTR Crossrail, which operates the Elizabeth Line, had warned of safety risks from the Sphere, saying the giant illuminated ads would make it difficult for train drivers to pick out signals vital for running trains at high speeds on a complex part of the network. Historic England was objecting over heritage concerns, even citing the Sphere’s impact on the view of St Paul’s Cathedral from all the way out at King Henry’s Mound in Richmond. A local cycle group had hit out at the amount of car parking planned for the venue. Neighbouring councils like Hackney and Greenwich were also throwing their weight against the Sphere.

Ceren describes the actual LLDC meeting, held in a room in the London Stadium, as “gruelling”, lasting over four hours. The document bundle handed out to attendees — the plans, the objections — was practically a book, standing at 390 pages. But when it finally came to the vote, the verdict meant heartache for the campaign: LLDC approved the construction of the Sphere, though with a few strings attached.

In some ways, the vote was bittersweet for campaigners. Every single councillor on LLDC’s planning committee had rejected the plans, validating their efforts to raise the alarm. But it wasn’t enough — the appointed members had all waved it through. Stop the MSG Sphere would react by calling the decision a “travesty of democracy”.

Ceren remembers it as “a massive low point, but also just like, of course they did. We were not surprised. But just what a blow. Five years of not being able to enjoy where I live, to enjoy my home, and just being scared of the prospect of the Sphere.”

Ultimately planners had a hard time turning down the business case for the Sphere. And MSG had promised big money. According to EY estimates commissioned by the company, the Sphere would have generated £2.5bn in London over its first 20 years. 4,300 jobs would be created by its construction, and a further 3,200 needed each year when it eventually opened. And for local businesses in Newham, they could expect an extra £50m in revenue to trickle down each year.

But the decision was especially hard to take, given what campaigners viewed as meagre concessions from MSG to their concerns. Most enraging was the offer of free blackout blinds for nearby residents to help mitigate against the Sphere‘s glare, including for Ceren. Anger was so high that other residents were threatening to “move out” in protest.

The battle wasn’t over, though. The sheer controversy of the Sphere meant someone else higher up the planning food chain would inevitably be called in — Sadiq Khan as London mayor or even Michael Gove, the UK housing secretary. All eyes were on what they’d do next.

Sin city

An unexpected blessing for the anti-Sphere campaign in London was the opening of the original in Las Vegas. As footage of its gargantuan displays spread, so did media interest in London’s copy. The campaign had already managed to garner a fair amount press attention in the years prior, but from September 2023, with the Las Vegas Sphere fully online, the number of reporters calling up to hear about MSG’s plans for London only grew.

Indeed, Stop the MSG Sphere hasn’t been afraid to dig up dirt on MSG from across the Atlantic throughout its five-year campaign. The Madison Square Garden Company is headquartered in the US and is most well known for the New York indoor arena that gives it its namesake, which hosts concerts and sports. Its executive chairman is James Dolan, an American businessman who also owns the New York Knicks basketball team. Other aspects of Dolan’s activities proved to be of particular interest to campaigners.

Right back at the London Sphere’s conception in 2018, sceptics were pointing out Dolan was a financial supporter of former US president Donald Trump, and arguing that concert-goers would, in effect, be funding him too. “We all know that the music community does not support Donald Trump,” was the take of Beverley Whitrick, the strategic director of the Music Venue Trust, which supports UK grassroots venues, when the Sphere plans were unveiled. “A lot of musicians and audience members will feel uncomfortable.” And then there was Dolan’s connection to serial sexual predator Harvey Weinstein — the MSG exec had been accused of knowing about Weinstein’s conduct while he sat on the board of the disgraced film mogul’s production company. Dolan even wrote a “sad song” over his guilt regarding Weinstein, though a spokeswoman for Dolan has previously said he was “confident that he acted appropriately in all matters relating to his time on the Weinstein board”. Both Trump and Weinstein stories are featured in a ‘News’ section on the Stop the MSG Sphere Campaign’s website.

Campaigners were then quick to jump on news things were going awry for the Las Vegas Sphere after launch. On November 8, it was revealed that the CFO of Sphere Entertainment Co had abruptly quit, after it was reported the company had lost $100m in its first quarter. “We could be left with a white elephant too,” warned Stop the MSG Sphere.

But another, behind-the-scenes moment was also key to reigniting campaigners' hopes in the months following the LLDC’s approval. In February 2023, Michael Gove had ordered any construction of the Sphere to be halted. This wasn’t by any means a reversal — the so-called ‘Article 31 holding directive’ just meant the housing secretary was considering whether to call the planning decision in and potentially hold a public inquiry. But for Stop the MSG Sphere, it started to look like the scales could be tipping in their favour.

A reversal

When news Khan was blocking the Sphere broke on Monday, November 20, 2023, campaigners were instantly delighted. They’d had some prior notice the mayor would be making a call that day, with the group’s account on X/Twitter posting a GIF of a nervous-looking Kermit the Frog in anticipation.

Initial elation gave way to caution though, knowing that Khan’s call wasn’t necessarily final. Gove might still have intervened, or MSG might have mounted a legal challenge. But the fate of London’s Sphere was sealed when MSG announced it would be selling the site. The company’s parting statement had a hint of venom: “While we are disappointed in London's decision, there are many forward-thinking cities that are eager to bring this technology to their communities. We will concentrate on those”. Dolan went further in an interview with the Standard, calling Khan’s decision “political” and saying: “It really is the end of the line for London. Why doesn’t London want the best show on earth?”

Officially, it’s the evidence presented to Khan by City Hall planning officers that’s won out, after engineering firm WSP helped put together a report on the Sphere. The mayor had been told that the illuminated dome would have caused “unacceptable harm to hundreds of residents” living nearby, with Ceren’s building, Legacy Tower, explicitly mentioned. The Sphere’s design, particularly its energy usage, was criticised, with officers saying it “does not achieve a high sustainability standard” and has “a bulky, unduly dominant and incongruous form” that would “fail to respect” the character of Stratford centre. Officers even spotted “significant errors and omissions” in MSG’s own assessment of the Sphere.

But unofficially, the Spy does wonder if politics may have played a part, at least a bit. Speak to campaigners and they’re clear on who they say has been their greatest allies: the Greens, not Labour. When the Labour mayor of Newham, Rokhsana Fiaz, posted a victory letter claiming the campaign against the Sphere had “been led by my administration” on social media, Stop the MSG Sphere curtly replied: “let's be truthful - this was a people-led campaign & it took a lot of work to get Labour officials to engage with us about it.” With a mayoral election around the corner in May 2024, and Khan’s lead on his Conservative rival at times looking tight, stopping Greens from weaponising the Sphere and stealing votes locally won’t be doing Khan any harm.

The future

“The NIMBYism on display and being so pusillanimously indulged here is as infuriating as the NIMBYism of those residents of central Soho who expect their streets to be silent and pubs closed by 10pm,” was the scorching take of political commentator Tom Harwood after Khan’s decision. “I would gently suggest that if someone were to want a slower, quieter, and unilluminated, life they should perhaps choose to live literally anywhere other than the centre of a bustling megacity.”

Many like Harwood have accused the campaign of NIMBYism in the wake of the Sphere’s rejection. But campaigners are adamant that was not what they were about. When asked by the Spy, cllr Higgins replies: “It's certainly not NIMBYism, right? Nobody chose to make Stratford their home expecting nothing to change.

“I really think people are making the unfortunate mistake of pattern-matching things they hear from elsewhere onto one of the youngest wards in the country where the vast majority of people are renters. This isn't a community that's been here for 40 years and very stuck in their ways, and doesn't want things to change. And I don't mean that pejoratively against those sorts of people. That's not what's going on here. It's a project that is seriously damaging to the community, that consists of severe opportunity costs for the use of the land, and where the process has been completely appalling.”

Cllr Higgins has a clear priority for the proposed site of the Sphere now — he wants affordable housing built there instead. “Newham has a massive temporary accommodation crisis, the highest number of children in temporary accommodation in the country,” he explains “And that's a crisis that this site could contribute to helping to solve. So I really hope that either the council or the LLDC or the [Greater London Authority] itself considers buying the site”. And if that doesn’t work out, he thinks a faith centre could be a good idea. “There's a shameful lack of access to faith institutions in the area considering the demographic makeup of Newham.”

Ceren says she’s also never been against building on the site per se — “I just didn’t think it would be the Sphere, of all things,” she says. But after five long years of fighting, she’s ready to enjoy her home. “It's been exhausting, it really has been so, so exhausting. But in terms of what's next — we're not letting our guards down completely.”

Absolutely brilliant reporting!